Tucker's Solstice Race Report

/S-H-I-T was the first word I learned how to spell. My mom taught me. I remember jumping up and down on the bed as she readied for work, a letter per jump.

“S-H-I-T. S-H-I-T. S-H-I-T!”

“Tucker, this is a word we don’t say or spell at school. OK?”

You can guess how that went. But my name only ended up in the kindergarten Dog House once when Wyatt, that little son of a bitch, ratted me out. I remember a conversation at home, but no punishment, so ubiquitous and versatile was the term. Twenty some years later it remains a top vocabulary word. Appropriately so.

When Ryne was in the process of hiring me to be a handler one of my references was kind enough to tell her that he thought I was going places. Later on, she told me in good humor that when he’d said that, all she could think was: “Ya, going places to scoop a lot of shit.”

As a handler, “What about all the poop?” is among the FAQs of family and friends. There are several ways to answer this. In person I just say, “We scoop it up and throw it in a big pile.” But this answer wants justice. I could do some real math but I won’t because even a number with a unit in the tons does little to satisfy the chore.

Well. Come along with me.

First of all, there’s a complex ranking system for poop-scoop-ability. It’s located in the heart of every poop-scooper and it takes into account temperature/surface/desiccation/tool/etc. Classification nomenclature is instinctual and often based on one’s mood — ranging from elaborate cusses to compliments that are usually reserved for a 5 year old’s art project.

At Ryno Kennel we use garden hoes and industrial dust-pans to do our scooping. Dare I say there is an art form to hoeing shit into a pan? That it can become a honed skill worthy of the resume? That it is healthy for the soul? Yes.

There is a poem by John Updike titled “Hoeing”. It’s first stanza goes:

“I sometimes fear the younger generation will be deprived

of the pleasures of hoeing;

there is no knowing

How many souls have been formed by this simple

exercise.”

I think of these lines as I excavate the likeness of a crystalline amethyst from the hard-packed snow. Tink-tink-tink travels the sound of mining efforts through the frozen air. I move to the next dog circle where Oryx is excitedly running around with a frozen poop in her mouth.

“Oryx, give that to me. Give it to me. Oryx. Oryx. Oryx. Fine, keep it.”

Onto the next circle. I look back to predictably see Oryx, poop in mouth, squatting for a fresh dump. She looks me in the eye, as they tend to do, and says, “What of it?” To twist Kurt Vonnegut’s refrain: So shit goes.

And so it does go into a sled which is then taken on a Sisyphean expedition up Shit Mountain — as it’s colloquially known. Look out Denali and mountaineers beware, there is a geological phenomenon in Two Rivers gunning for Alaska’s highest peak. Just know that when I use “shit-pile” as a metric, I’m thinking of a shit-pile that has footholds on its vertical face.

Ryne’s asked Sam and I to write blurbs about the recent Two Rivers 50 mile Winter Solstice Race.

How was the race? How’d you make out? It was good, we placed in the middle. But for the Ryno Kennel dogs the term “race”, in this case, is a misnomer. As a handler, that misnomer is one of the more difficult things to communicate to family and friends about what we do. If I were to describe the details of my Solstice Race — how the dogs ran and looked, what the trails were like, how cold it was — it would sound like a description of a 50 mile training run on the trails right behind the cabin, holding the dogs' pace steady, always under 10mph.

Two big differences, though: the commotion of the start and there were more teams on the trail than usual. We have a bunch of two-year-old dogs who are into the heavy mileages but have no race experience, the more exposure they can get to race-like conditions the better. As for the start, they did awesome. And as to running 50 miles on trails they are getting a little bored of, they had fun. With all the teams passing there was stimulation and excitement in the air and around the corners. At the finish, we pulled into the line, Ryne wrestled my race bib off of me, and instead of turning into the parking lot with all the dog trucks we continued straight on the trail, headed home.

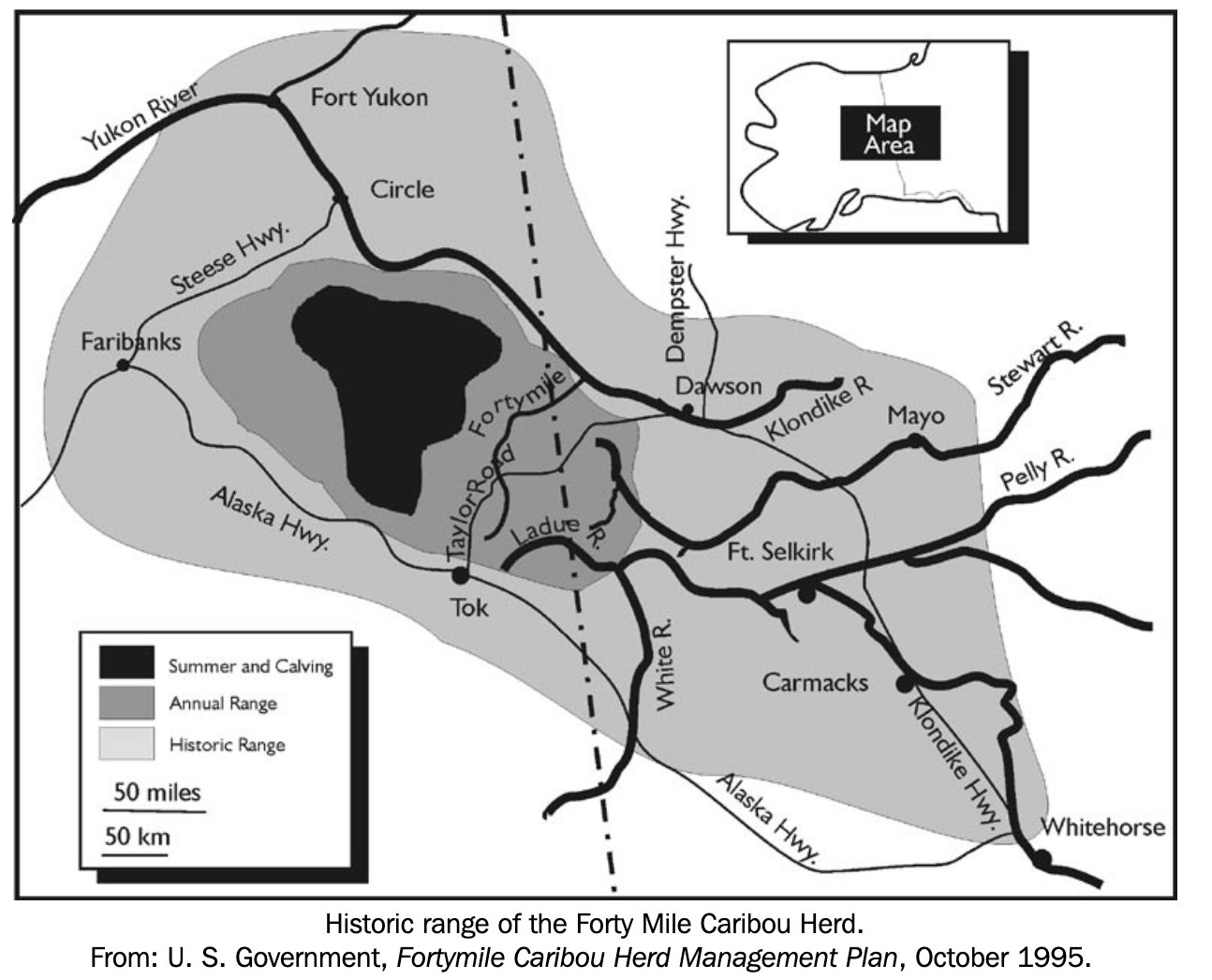

For some mushers, these races are an excuse, not necessarily to race dogs, but to run dogs. Whether that be in Two Rivers, or on the Denali Highway, in the Copper Basin, or on the Dawson Trail. For other mushers, certain races are opportunities to train dogs for future races where they intend to be competitive. This year, Sam and I are in both camps. With Ryne not racing she’s effectively become a super handler for Sam and I at our respective races.

Really, I’m in the same boat as our two-year-old dogs. It was just as valuable for me to experience a race start on the sled. But ultimately, what stood out to me were the people holding my gangline steady, walking the team to the start. Ryne, Derek, Matt Hall, and a handler from another kennel. Ryne passed along this wise line earlier in the year: “You’ve gotta deal with the shit to do the cool shit.” And that’s the gist of who was holding out my gangline at the race start, people who have dealt with a lot of Sisyphean shit to help me experience some stuff that’s pretty damn cool.

“Choo-choo, the poop train is leaving,” I say to Sam as she brings over a final dustpan load of the evening's mining efforts. I have the poop-sled’s rope in hand and as she begins to dump the pan I pull the sled away at the last second —a trick I learned from Simon last year, to keep shit interesting.